The Whistler Who Hacked the World: The Joseph Engressia Story

Joseph Engressia could make free phone calls to anywhere on Earth with nothing but his voice. No tools, no equipment—just a whistle at precisely 2600 Hz. This is his story.

The Discovery

Engressia was born blind. Like many people with congenital blindness, he developed exceptional hearing and musical ability to compensate. He had perfect pitch and could reproduce any sound he heard with exact precision.

When Joseph was nine years old, something strange happened during a phone call. He whistled into the receiver, and the line went dead. That whistle hit 2600 Hz—the exact frequency AT&T used to control their telephone switching systems.

Joseph started experimenting. He learned to control the phone system entirely by whistling. He could interrupt calls, transfer lines, and manipulate connections. He didn't know it yet, but he'd just become one of the first phone phreaks—hackers who exploited telephone networks.

The Phone Tricks

His classmates loved it. Joseph could whistle the control tones from memory. Want a free long-distance call? Ask Joe. He'd whistle the sequence and open the line.

But Joseph wasn't just showing off. He was learning. He ordered technical literature on telephony from libraries for the blind—hundreds of pages of it. He absorbed everything about how telecommunications worked. The technology fascinated him more than the free calls.

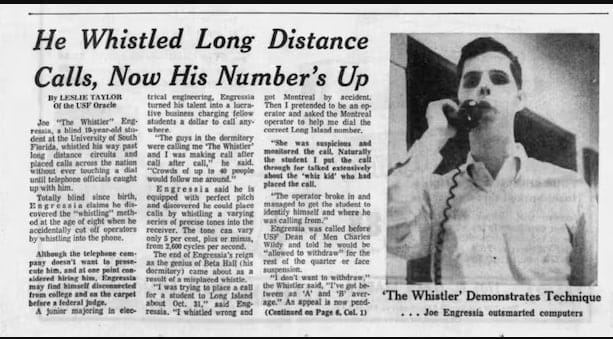

The First Bust

After high school, Engressia enrolled in university to study philosophy. He'd mastered long-distance and international calls by then, and he started offering the service to fellow students for $1 per call. He wasn't doing it for money—he charged basically nothing. He did it because it interested him.

That's what got him caught. In 1968, after an investigation, the university expelled him and fined him $25. He later got reinstated and finished his degree.

The Ethics of Phreaking

Here's what separated Joseph from other phreaks: he never used his skills to harm anyone. He cared about the technology, not theft or fraud. He shared his knowledge freely, teaching others how phone systems worked. But he always insisted on one thing—use it ethically.

By the early 1970s, Joseph had become a legend in the phreaking community. The FBI started watching him, along with other prominent phone hackers.

The Esquire Article

In 1971, Esquire magazine published an article about "phone hippies" that featured Joe Engressia. The piece brought phreaking into public view—and onto the FBI's radar in a serious way.

Joe was arrested again, this time on telephone fraud charges. He received community service as his sentence.

The Phone Company Job

In 1975, Joseph decided to quit phreaking completely. He moved to Denver and tried to find work, but his blindness made it difficult.

Then something remarkable happened. The same FBI agents who'd pursued him for illegal activity helped him get a job. Through their referral, Joseph joined the technical support team at Mountain Bell telephone company. He configured equipment and solved problems on subscriber lines. He later said he could do more than some of his colleagues who held engineering degrees.

The Final Years

The phone company work eventually bored him. Joseph quit Mountain Bell, moved to Minnesota, and lived on disability pension. But he didn't stay idle.

From his home, he set up a telephone service called "Stories and Stuff." He told funny stories to seriously ill people over the phone. He acted as a consultant for blind children. He found ways to help others using the same telephone system he'd once exploited.

The End of an Era

On August 8, 2007, medics found Joseph Engressia dead in his home. The cause was congestive heart failure.

With his death, many believe the era of phone phreaks truly ended. Joe was one of the last "techno-hippies" from the 1970s—people who explored technology out of pure curiosity, not malice.

What His Story Teaches Us

Joseph Engressia's life shows us something important about the relationship between curiosity and ethics in technology. He had a gift that let him exploit a major telecommunications system, and he used it to learn, not to steal. When he taught others, he insisted they follow the same code.

The irony is perfect: the FBI agents who arrested him later helped him get legitimate work doing exactly what he'd been doing illegally—fixing phone systems. They recognized his talent was real, even if his methods had been wrong.

In today's cybersecurity profession, we see the same pattern. Many skilled security researchers started by exploring systems they probably shouldn't have touched. The difference between a criminal and a professional often comes down to intent and restraint.

Joseph wanted to understand how things worked. That curiosity, channeled properly, is exactly what makes great security professionals. His story reminds us that talent can be redirected, that curiosity isn't criminal, and that the people who understand systems best are often the ones who figured them out from the outside.