The Mic-E-Mouse attack turns an ordinary mouse into a listening device

Researchers at the University of California, Irvine (UC Irvine) have demonstrated a surprising side-channel attack: high-DPI optical mice can pick up surface vibrations caused by speech, allowing attackers to reconstruct nearby words with troubling accuracy.

Modern gaming and professional mice use ultra-sensitive optical sensors (20,000 DPI and above) that track tiny motions of the desk surface. When someone speaks nearby, those sound waves make the table surface vibrate just enough for the sensor to register micro-oscillations. The UC Irvine team calls the technique Mic-E-Mouse — a low-cost, low-profile way to turn a mouse into an improvised microphone.

How the attack works

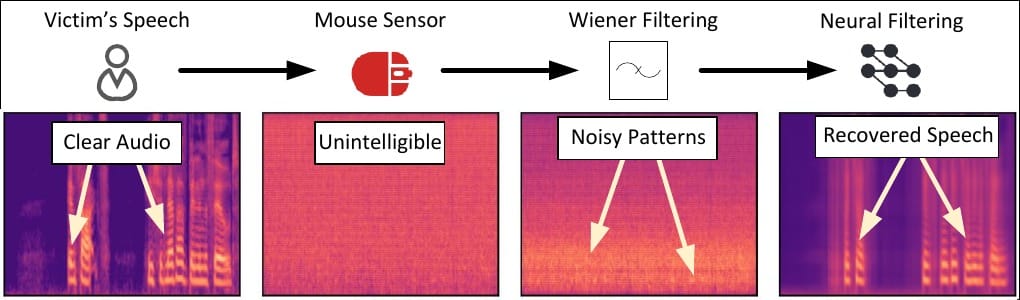

The researchers show that raw mouse movement data — initially noisy and scrambled — can be transformed into intelligible audio through a multi-stage processing pipeline. First, the raw telemetry is cleaned with traditional digital signal processing (for example, a Wiener filter). Next, a neural model further denoises and reconstructs the speech waveform. The result: near-clear audio derived solely from mouse motion.

In tests, the team boosted signal quality by as much as 19 dB, and speech-recognition performance on standard datasets ranged between 42% and 61%. While not perfect, those accuracy figures are high enough to expose sensitive spoken information in many real-world settings.

No malware required

A particularly worrying aspect of Mic-E-Mouse is its practicality. The attack does not require privileged system access or custom malware. It only needs mouse packet data — information that ordinary applications (video games, graphic editors, or even web apps in some scenarios) can legitimately request to support high-speed input. Because the data collection uses standard telemetry, it remains invisible to the user while reconstruction is performed remotely by the attacker.

“Using only a vulnerable mouse and the victim’s computer, on which compromised or even harmless software is installed (in the case of a web attack), one can collect mouse packet data and then extract audio signals from it,” the researchers write.

Threat scenarios and mitigations

Mic-E-Mouse is most practical where an attacker can run code that captures mouse telemetry — for example, a malicious or compromised application, or a web page that can access high-frequency input data. Public Wi-Fi and shared office environments increase attacker opportunity, but the core risk lies in lax controls over which processes and sites can read raw human interface device (HID) data.

Potential mitigations include:

- Restricting access to raw HID/mouse telemetry at the OS level and monitoring which apps request high-frequency input.

- Limiting telemetry sent by applications and avoiding unnecessary high-precision mouse modes in shared or sensitive environments.

- Vendor hardening: mouse and driver vendors should consider rate-limiting or noise-injection for non-movement telemetry and clearly document what telemetry is exposed.

- User awareness: minimize sensitive conversations near devices in environments where untrusted apps run.

Why it matters

Mic-E-Mouse highlights how commodity hardware — designed for speed and precision — can be repurposed into an information-leak channel. As peripheral sensors become more precise, attackers will look for new ways to exploit that sensitivity. The research underscores a simple truth: hardware features intended to improve user experience can also widen the attack surface if telemetry and access controls are not carefully constrained.