DroidLock Android Malware Combines Screen Locking, Remote Access, and Ransom Demands

Security researchers at Zimperium identified Android malware that locks victims' device screens while establishing comprehensive remote control capabilities. The threat, named DroidLock, demands ransom payments to unlock devices while maintaining VNC access for data theft and surveillance.

DroidLock represents an evolution beyond simple screen-locking ransomware. The malware combines device lockout tactics with remote administration tools, creating a threat that persists even if victims regain device access through technical means.

Targeting Spanish-Speaking Users

DroidLock campaigns focus on Spanish-speaking users, distributing malware through websites disguised as legitimate application sources. This geographic targeting suggests attackers either operate within Spanish-speaking regions or specifically pursue victims in these markets for reasons Zimperium hasn't disclosed—possibly language capabilities, payment method preferences, or law enforcement jurisdiction calculations.

The distribution method relies on social engineering rather than exploiting Android vulnerabilities. Malicious websites impersonate trusted app sources, convincing users to manually install APK files outside Google Play Store protections.

Dropper-Based Infection Process

The infection chain begins with a dropper application that serves as the initial payload. This dropper tricks victims into installing the main malicious component, which then requests critical Android permissions: Device Administrator and Accessibility Services.

These permission requests represent the critical moment where users can stop the infection. However, malicious apps often disguise permission requests as legitimate requirements, claiming they need administrative access for security features or accessibility controls for user interface improvements.

Once granted, Device Administrator and Accessibility Services permissions provide extensive system control. The malware can lock devices, modify PIN codes, change passwords, and alter biometric authentication settings—effectively locking legitimate owners out of their own devices.

Android's security model assumes users make informed decisions about permission grants. DroidLock exploits the gap between what permissions technically allow and what users understand they're authorizing.

Comprehensive Remote Control Capabilities

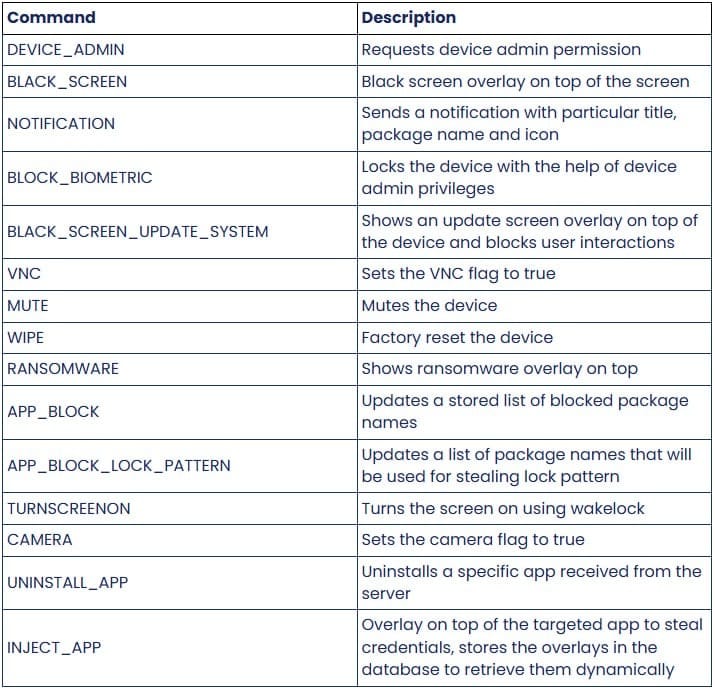

DroidLock supports 15 distinct commands, giving attackers granular control over compromised devices. Capabilities include sending notifications, overlaying the screen, muting the device, performing factory resets, activating cameras, and deleting applications.

The VNC (Virtual Network Computing) integration stands out as particularly invasive. This remote desktop protocol allows attackers to view and control device screens as if physically holding the phone. Combined with pattern unlock theft, VNC access enables attackers to operate devices remotely during periods when victims aren't actively using them.

The malware specifically targets Android's graphical unlock patterns through overlay attacks. When users attempt to unlock their devices, DroidLock displays a fake pattern entry screen loaded from the malicious APK's resources. Users draw their patterns thinking they're authenticating to Android, but they're actually submitting credentials directly to attackers.

This captured pattern data serves two purposes: immediate device access for the current session, and credentials for future VNC connections when victims aren't monitoring their devices.

Ransom Mechanism Without Encryption

Unlike traditional ransomware that encrypts files, DroidLock simply threatens data destruction. The malware displays ransom demands through WebView overlays immediately after receiving signals from command and control servers.

Victims receive instructions to contact attackers via Proton Mail addresses—encrypted email services that provide operational security for cybercriminals. The ransom demands include 24-hour deadlines, threatening file deletion if payment doesn't arrive within that window.

The lack of actual encryption represents both good news and bad news for victims. Good news: data remains intact and potentially recoverable through technical means. Bad news: attackers maintain remote access and can follow through on deletion threats if they choose.

Additionally, attackers can lock device access by changing unlock codes, creating immediate operational impact regardless of whether they delete files. Victims lose phone functionality—calls, messages, banking apps, two-factor authentication—even if their stored data remains technically intact.

Google's Detection Response

Zimperium shared threat intelligence with Android Security teams, enabling Play Protect to detect and block DroidLock on updated devices. This means current Android versions with active Play Protect should identify the malware and prevent installation.

However, this protection only helps users who maintain updated devices and have Play Protect enabled. Older Android versions, devices that don't receive security updates, and users who disable Play Protect remain vulnerable.

The Android ecosystem's fragmentation creates persistent security challenges. While Google quickly updates Play Protect definitions, millions of devices run older Android versions that manufacturers no longer support with security patches.

In My Opinion

DroidLock demonstrates how Android's permission model creates security trade-offs that favor functionality over security. Device Administrator and Accessibility Services provide legitimate purposes—enterprise device management and assistive technologies for users with disabilities. Yet these same permissions enable comprehensive device compromise when granted to malicious applications.

Per the research findings from Zimperium, the combination of screen locking, VNC access, and pattern theft creates multiple attack vectors that persist even if victims partially remediate the infection. Removing the screen lock doesn't eliminate VNC access. Changing unlock patterns doesn't revoke Device Administrator permissions. Each malware capability requires separate remediation steps that most users won't know how to execute.

The geographic targeting of Spanish-speaking users suggests organized operations rather than opportunistic malware distribution. Attackers made deliberate decisions about target demographics, possibly based on payment likelihood, technical sophistication assessments, or law enforcement risk calculations.

The dropper-based distribution through fake app websites exploits user behavior patterns that security education has struggled to change. Users continue installing APKs from untrusted sources despite years of warnings about these risks. The behavior persists because legitimate reasons exist for sideloading apps—regional restrictions, app unavailability, corporate applications, and open-source software not distributed through Google Play.

Attackers exploit this legitimate use case, creating websites that appear trustworthy enough to convince security-conscious users to make exceptions to their usual caution. The fake legitimacy might include professional website design, fake reviews, or impersonation of known app developers.

The ransom mechanism without encryption reveals attacker priorities. Traditional ransomware encrypts data because decryption keys provide guaranteed value to victims—pay the ransom, receive the key, recover files. DroidLock's deletion threats provide less assurance. Even if victims pay, attackers might delete files anyway. The lack of encryption suggests either that attackers haven't developed encryption capabilities or that they find screen locking and device control sufficiently profitable without the technical complexity of encryption implementation.

The VNC access component transforms DroidLock from simple ransomware into persistent spyware. Attackers can monitor device activity, steal credentials from banking apps, intercept two-factor authentication codes, and access any data displayed on screen. This capability potentially generates more value than one-time ransom payments.

Organizations should recognize that employee personal devices running DroidLock create corporate security risks. If employees access corporate email, Slack, or other business systems from compromised personal phones, attackers gain visibility into corporate communications and potentially access to corporate accounts through stolen session tokens.

The Android security model's reliance on user permission decisions creates fundamental challenges. Most users lack technical knowledge to evaluate whether requested permissions align with app functionality. Malware developers exploit this by requesting permissions that sound plausible—"accessibility services to improve user experience" or "device administrator for security features"—even when these permissions enable comprehensive device compromise.

Google's Play Protect detection helps, but only for users with updated devices and active protection. The Android ecosystem's fragmentation means millions of devices will remain vulnerable to DroidLock and similar threats regardless of Google's security updates.

The practical advice about not installing APKs from untrusted sources represents sound guidance that users won't universally follow. Security recommendations that conflict with user needs or workflows achieve limited adoption. A more realistic approach acknowledges that some users will continue sideloading apps and focuses on harm reduction—verifying APK signatures, researching sources before installation, and carefully reviewing permission requests.

DroidLock succeeds because it exploits multiple weaknesses: social engineering for initial infection, Android's broad permission grants for device control, user confusion about permission implications, and ecosystem fragmentation that leaves devices unprotected. Addressing any single weakness doesn't solve the problem—defense requires improvements across the entire attack chain.