ColdRiver Deploys ClickFix Attacks and Fake CAPTCHAs in New Campaign

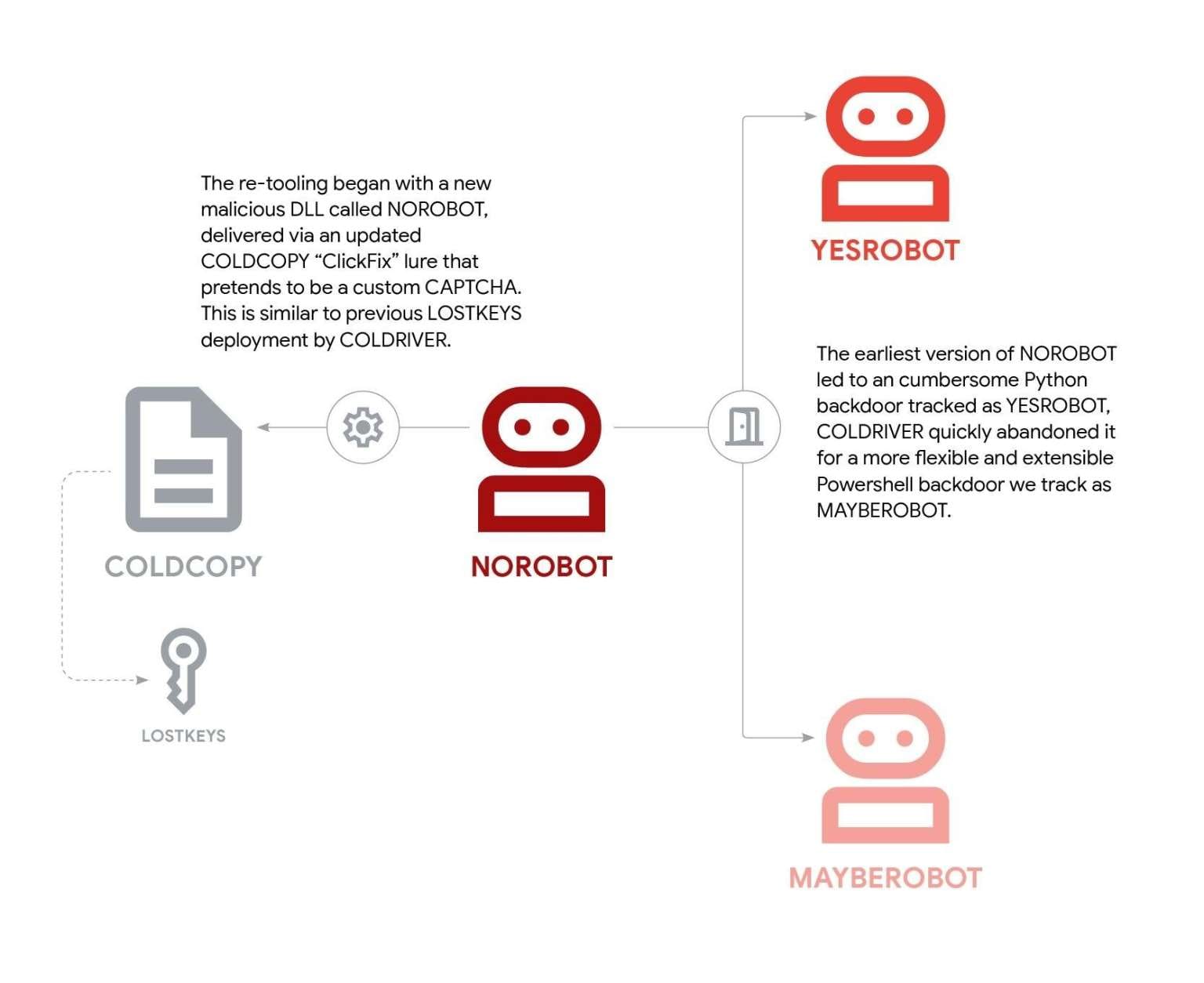

Researchers from Google Threat Intelligence Group (GTIG) report that the Russian-speaking threat actor ColdRiver has stepped up its activity, adopting new malware families—NoRobot, YesRobot, and MaybeRobot—delivered through complex, socially engineered ClickFix attacks.

How ClickFix Works

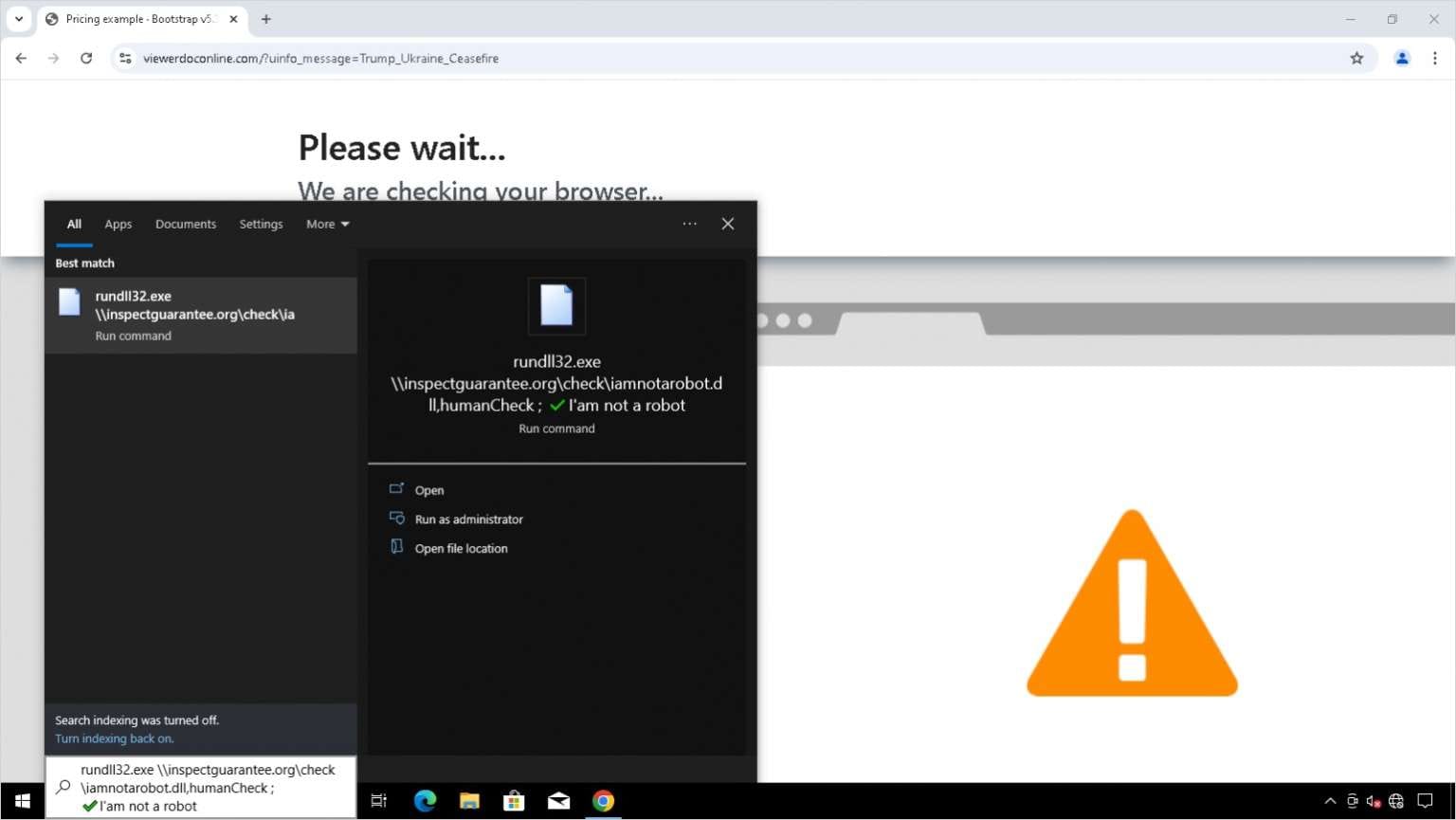

ClickFix attacks rely heavily on social engineering. Victims are lured to malicious websites and tricked into copying and executing PowerShell commands in their own terminals. In other words, users unknowingly infect their own systems manually.

Attackers often frame the command execution as a way to fix website display issues or as a step in solving a fake CAPTCHA.

While most campaigns target Windows users, analysts have already observed variants aimed at macOS and Linux systems. According to ESET, the use of ClickFix as an initial access vector surged 517% between the second half of 2024 and the first half of 2025.

From LostKeys to the “Robot” Family

ColdRiver—also known as UNC4057, Callisto, or Star Blizzard—previously relied on the LostKeys malware, which was detailed in a GTIG report in May 2025.

LostKeys was used in espionage campaigns against Western governments, journalists, think tanks, and research organizations. It collected data from predefined directories and file types.

Within a week of GTIG’s public disclosure, the group abandoned LostKeys and began using new tools: NoRobot, YesRobot, and MaybeRobot.

NoRobot: Fake CAPTCHAs and Registry Persistence

The first of the new trio, NoRobot, is a malicious DLL delivered through ClickFix attacks and fake CAPTCHA prompts. Victims believe they are completing a verification process, but instead launch the DLL via rundll32.exe.

Zscaler analyzed NoRobot in September 2025, naming the campaign BaitSwitch and the payload Simplefix.

GTIG researchers note that NoRobot achieves persistence by modifying the Windows registry and creating scheduled tasks. Early variants also downloaded Python 3.8 for Windows to enable deployment of the Python-based YesRobot backdoor.

However, this approach was short-lived: installing Python left a visible forensic footprint, drawing attention to the infection. ColdRiver soon replaced YesRobot with a PowerShell-based backdoor dubbed MaybeRobot (also referred to as Simplefix by Zscaler).

MaybeRobot: A Minimalist Backdoor

Beginning in June 2025, ColdRiver introduced a streamlined NoRobot variant that delivered MaybeRobot directly. This simplified backdoor supports only three commands:

- Download and execute payloads from a given URL

- Execute shell commands through the command line

- Run arbitrary PowerShell code blocks

After execution, MaybeRobot sends operation results to ColdRiver’s command-and-control (C2) servers, giving attackers feedback on infection success.

Researchers believe MaybeRobot’s development is now largely complete, and that ColdRiver has shifted focus toward making NoRobot stealthier and more resilient.

Complex Delivery Chains and Split Encryption

GTIG analysts highlight that ColdRiver continues to experiment with delivery complexity—moving from simplified to multi-stage chains.

Recent samples use split cryptographic keys distributed among different components, meaning the final payload can only decrypt successfully when all parts are combined.

“This was likely done to complicate forensic reconstruction,” GTIG wrote. “If even one component is missing, the payload cannot decrypt correctly.”

Campaign Activity and Targeting

ColdRiver campaigns involving NoRobot and related payloads were active between June and September 2025.

The group primarily uses phishing emails to deliver initial lures, though the motivation for its recent shift to ClickFix remains unclear.

One working theory suggests that ClickFix is being used to reinfect previously compromised targets, such as individuals whose emails or contact lists were stolen in earlier phishing operations.

“The goal may be to collect additional intelligence directly from their systems,” the report concludes.

Analysis

ColdRiver’s pivot from LostKeys to the “Robot” malware family shows a familiar pattern among state-linked espionage groups: rapid tool turnover after exposure, persistent social engineering, and ongoing refinement of infection chains.

By exploiting human behavior—convincing victims to run commands themselves—the group sidesteps traditional security controls.

The evolution from complex infection frameworks to deceptively simple delivery methods illustrates ColdRiver’s adaptive strategy: lowering technical barriers while maintaining operational effectiveness.